Parasocial Marketing

The post-modern and post-pandemic society we live in is bombarded with content. The inception of the internet and, more recently, the surge of influencers and independently-produced content creation beyond legacy media, have shifted the way we interact with the world, brands and other people. So much so that the lines of real life and online reality, and content and advertising have blurred. Now, we follow other strangers’ lives through our screens, even though sometimes we may feel we know them on a personal level. And most of the time, these strangers are also human billboards or entrepreneurs who sell us stuff, which is known as parasocial marketing. We’re going to explore this new way of doing marketing with real-life examples showcasing successes and failures.

What Is Parasocial Marketing?

I like to describe parasocial marketing as a byproduct of post-modern capitalism and social media voyeurism. However, the “dictionary” definition states that it is the active effort brands make to take advantage of the concept of parasocial relationships, that is, the one-sided and non-reciprocal connection between media personas (in this case, the characters fabricated by the writers and producers) and regular folks, to build a stronger connection between companies and their audience. This term was coined by Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl in 1956 to describe the intimate connection people developed with actors and the characters they played on their favourite TV shows. One of the main findings of this study is that these types of interactions can change behaviours and trigger purchases of products related to the persona.

With the arrival of the internet and social media, this concept has evolved and now requires a more active role from the media personas in the form of responding to comments, talking to viewers during a live stream or asking questions the community wants the persona to answer, for example. The persona also controls the parasocial relationships of our era through their ultimate free will of choosing what to show to their audience (even if the audience requests something) and the use of the tools of the social media platform they’re using, some examples of this include comment filters, content posting schedule, choosing which comments to reply to and blocking users if the persona isn’t comfortable with their behaviour. These interactions may also be fabricated by the creator’s staff, publicists or a PR team to make them seem “real.”

As you can probably imagine, this type of marketing is intertwined with influencer marketing, as studies have shown that the parasocial relationships customers have with influencers and content creators can positively impact brand trust, purchase intentions and brand reputation. But nowadays, the effectiveness of this type of relationship decreases with traditional celebrities like Angelina Jolie and Anne Hathaway because they’re not considered “regular people” who became famous online for sharing their mundane activities or their knowledge of a specific niche, such as fitness, parenting, beauty, fashion, gaming, and more. However, the fabricated nature of the influencer’s “online persona” remains the same, as some of the content they put out may be manufactured for engagement purposes.

Leveraging Parasocial Relationships With Influencers

The most prevalent way businesses use parasocial marketing is by working with influencers. We’re not going to delve into the ins and outs of influencer marketing here (you can check out this blog for that,) but we are going to discuss some relevant examples that show to what extent parasocial relationships can influence consumers’ behaviour.

Tween and teen one-size-only clothing brand Brandy Melville (or just Brandy, as their customers call it) hired 17-year-old TikToker Allegra Pinkowitz as a clerk at their store in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood. They have had great success at it: Girls wait in line with their parents to get a glimpse of their favourite influencer or even a selfie with Allegra — and, of course, to buy a tank top or two.

Long lines to enter the Brandy Melville store are a common sight in SoHo. (Photo credit: @myphotojourneybegins on Instagram.)

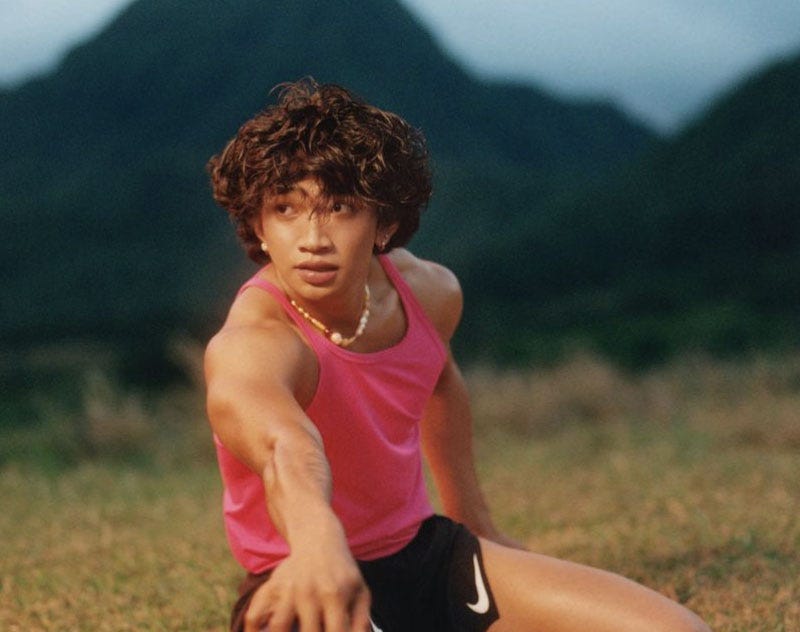

Another example is collaborations in which brands launch products or make campaigns with an online celebrity endorsing them. This is the case of Bretman Rock, a Filipino-American, Hawaii-based influencer who started in the beauty niche and branched out by sharing his fitness, fashion, and personal reflections with his audience. He is known online for his bold personality, humour, openness, and unfiltered honesty, which gave him millions of followers across the main social media platforms.

In 2020, Bretman collaborated with makeup brand Wet n Wild to launch Jungle Rock, a limited-edition collection inspired by his Filipino roots and tropical lifestyle in Hawaii. The collaboration was a success for Wet n Wild because the well-thought-out branding and packaging reflected Bretman’s heritage and aesthetic.

In an interview with Stylecaster, the then-21-year-old stated that the partnership was a no-brainer: “I live for Wet n Wild and everything the brand stands for. I feel like our brands are very similar. Like, I’m outspoken. I don’t follow the f**king rules. I’m talking about Wet n Wild like it’s a friend of mine, but that’s really it.” The Jungle Rock collection sold out quickly, and it caused big online buzz on YouTube and TikTok, and it gave Wet n Wild social accounts a spike in engagement due to crossover with Bretman’s audience.

Another successful collaboration with Bretman was Nike’s Be True Pride campaign in 2021. This recurrent campaign aims to celebrate and create more inclusive spaces in sport for the LGBTQIA+ community, and Bretman’s inclusion was another “no-brainer” because he didn’t just wear Nike; he embodied the campaign’s message of LGBTQIA+ pride and authenticity.

With “Be true to yourself” and “Strength has no gender” as core messages, the 2021 The Be True campaign gained quite a bit of traction online. (Source)

Campaigns with influencers work because their parasocial bonds make their followers emotionally invested in their success, turning product launches into shared wins. Products are also seen as an extension of the influencers and internet personalities we like. That’s why in the “clout economy” that has made views and likes currency, parasocial marketing is more prevalent than ever.

However, working with influencers can be a double-edged sword for brands, because the brand’s reputation depends on the influencer’s reputation and ethics. When a content creator’s behaviour becomes problematic, the brands they work with can be collateral damage in their controversies. That’s why, to mitigate the risk of influencers fans turning away from them thanks to a scandal, brands are instead trying to establish unbreakable parasocial relationships between them and their consumers. The brand wants to forge a connection so close that it won’t be disrupted by an influencer’s day-to-day choices and behaviour.

Brands Want to Be Your Bestie

I know that consciously thinking about the idea of being friends with a corporate identity may seem strange. Still, you may have a close relationship with some of your favourite brands without even realizing it. This is more likely to be the case the younger you are. As mentioned above, younger generations like Gen Z, Gen Alpha and even younger Millennials have shown to be more prone to fall into a one-sided friendship with their favourite brands, due to being chronically online, and because they’re more prone to feel lonely and isolated.

Brands know it, that’s why they’re intentionally using their audiences’ slang, memes, viral events and jokes in their messaging, copy and visual identity in an attempt to make the audience feel like the brand is “one of them” by using their social media team to fabricate a familiar brand persona that resonates with their customers. This form of online interaction between people and companies doesn’t have much research behind it because it’s pretty new, but marketing researchers have started to shed some light on an efficiency in provoking parasocial interactions and establishing a closer relationship with audiences by being more casual and relatable.

Some studies from the last decade have shown that brands that use more casual language and address their audience directly in a conversational way tend to be more attractive to consumers, have higher rates of engagement and brand loyalty, and evoke stronger parasocial interactions as consumers feel they are part of a community. Creating that sense of community is the main goal of every parasocial interaction effort, as the people who feel part of said “community” perceive it as an extension of the persona, in this case, the brand itself.

People build parasocial relationships with brands when they’re seeking expert knowledge in a particular niche, too, just like we follow a certified personal trainer influencer if we want to know more about fitness from a source perceived as credible. Furthermore, smaller brands that the audience feels closeness and familiarity with, for example, a local-based beauty salon chain that has one or more locations throughout a city, tend to have more success at establishing parasocial bonds with consumers living closer than bigger corporations.

Now that we have outlined the theory behind parasocial marketing for brands let’s look at some examples.

Real-Life Parasocial Marketing By Brands

The Good

Duolingo

Language learning app Duolingo’s mascot, Duo, has its persona on TikTok, and people love it. People became attached to the owl’s funny, chaotic, and sometimes “aggressive” reminders to do a lesson on Duolingo to keep the users’ streak. Users began to interact with Duo as if it were a real friend (or frenemy), deepening their attachment to the brand. The quirky and sassy personality the brand gave to Duo also allowed them to hop on viral trends and sounds on TikTok without looking forced.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Duo’s dancing to Katseye’s viral song “Gnarly.”

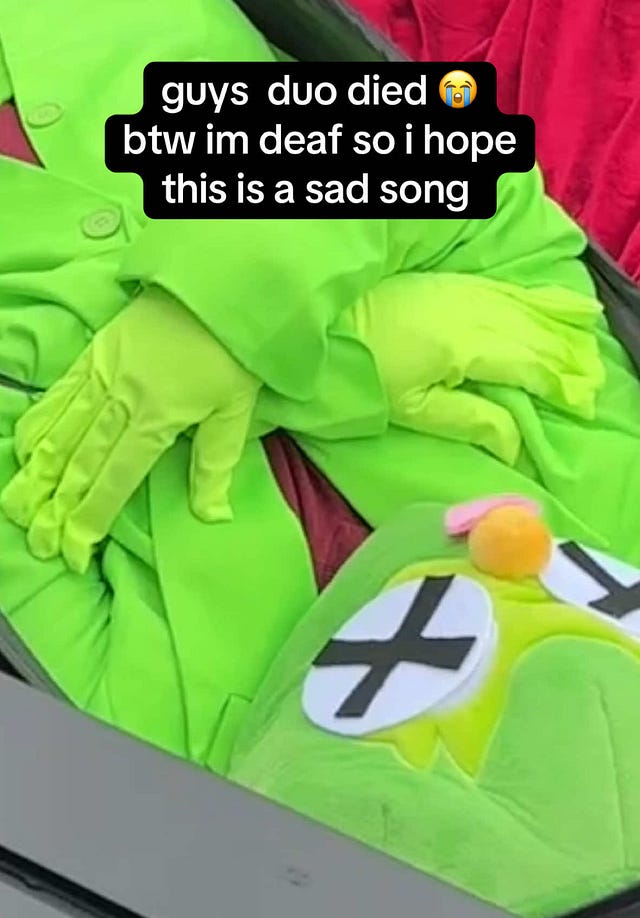

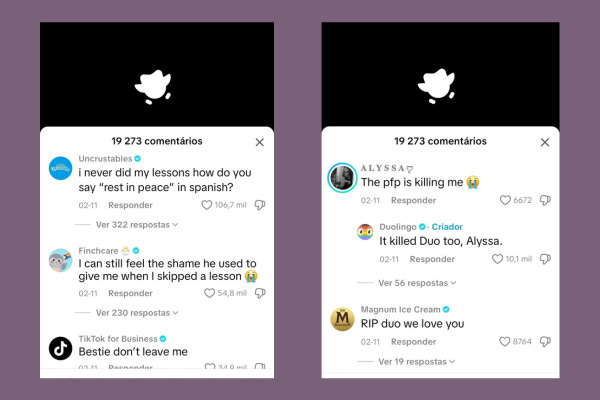

One of the recent campaigns that went viral on TikTok and other social media platforms was the “death” of Duo due to people not doing their daily lessons in February 2025. The campaign started with the announcement of its passing. It continued with videos showing its funeral showcasing its eyes as Xs and a tongue out, and its actual cause of death: Being hit by a Tesla Cybertruck (a.k.a the ugliest car ever created). The campaign was a whole theatrical stunt showing “investigation” teases and cryptic videos that went so viral that other brands hopped in to get some of the clout.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Dua Lipa was Duo’s “unrequited love interest” and also joined the mourning.

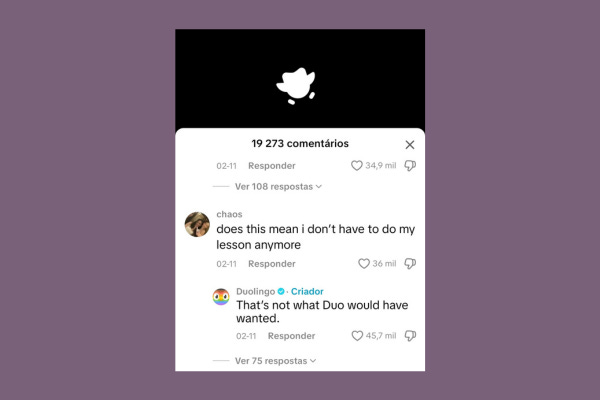

The campaign’s ultimate goal was to, of course, make people use Duolingo. The brand launched an interactive challenge: users worldwide needed to collectively earn 50 billion XP by completing lessons to bring Duo back from the dead. The challenge showed the XP gathered by country, creating a friendly global competition.

Two weeks later, the Duolingo users hit the goal; Duo “resurrected”, and the company wrapped up the campaign tied back to core brand goals: encouraging consistency to learn languages and boosting longtime users to re-engage.

On a side note, the campaign was masterfully global but adapted to each culture:

In Japan, Duo never died due to the cultural sensitivity to death. Instead, it had a “power-up.”

In Germany, Duo’s revival had a spooky occult-cult twist.

In Brazil, the campaign also included McDonald’s and featured telenovela-inspired videos.

The death of Duo was more than a funny gimmick: It was a brilliant parasocial storytelling and community mobilization built on a foundation of a distinctive face of the brand and voice. It sparked massive cultural buzz, app engagement, and joyful communal participation with maximum virality.

The Bad

Prime

Prime is a sports and energy drinks brand founded by influencers and former boxing rivals Logan Paul and Olajide “KSI” Olatunji; both have several million followers on YouTube and Instagram and an audience of mostly male kids, teenagers and young adults. Paul and KSI launched Prime in January 2022, and they expressed their intention to go against big competitors like PepsiCo’s Gatorade and Coca-Cola’s Powerade, selling the story of two rivals turned into friends and business partners that joined forces to create “better” energy drinks and challenge the “bad” corporations’ position in the market.

Their audience touched and excited for the new venture of their favourite influencers, went into a frenzy to get the drinks the day they hit the stores: Both fans and resellers eager to make bank waited in long lines, trampled each other and started fights in many stores Prime was being sold.

But the Prime craze didn’t end there. Many YouTubers hopped into the trend and made over-the-top challenges with Prime as the protagonist that not only served as free ads but also as tributes to Prime’s founders, including building cars, shooting TV commercials or the video below in which the creator built five giant Prime bottles and travelled with them to London to deliver them in person.

However, Prime has two fatal flaws: It’s a bad product, and Logan Paul and KSI are well-known for exploiting their impressionable audience. Prime’s taste had mixed reviews, including celebrity chef Gordon Ramsey’s that stated that drinking Prime was “like swallowing perfume.” The drink is also very high in caffeine, making it unsafe for kids and teenagers. It has been banned from several schools in Australia and the UK, prohibited from being sold to minors in Latvia, banned for sale in the Netherlands, and has had issues entering other countries due to its high concentration of vitamin A.

Lastly, in 2023, an American consumer filed a lawsuit against Prime alleging undisclosed harmful levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl (PFAS) synthetic chemicals known to be bad for health.

I chose this example not because it wasn’t successful but because it showcases the dark side of parasocial marketing: manipulation and exploitation. Parasocial bonds can detrimentally influence people’s behaviour negatively, including fighting over a sports drink, impulse buying and overconsumption that can lead to a shopping addiction, financial problems, and health issues from consuming questionable products due to parasocial interactions.

As I mentioned above, Logan Paul and KSI have a history of exploiting their impressionable audience, including selling overpriced merch, creating and pushing crypto scams, overhyped pay-per-view boxing matches that don’t deliver what they promised and the Prime partnership itself, which was labelled as manufactured because before they portrayed a “rivalry” to keep the hype around their matches high and, you guessed it, gain more money.

In Closing

Parasocial marketing is a powerful tool that can get you great results, but it can be harmful when used by people with questionable intentions. It leverages the emotional bonds fans form with influencers or mascots, allowing brands to foster loyalty and build communities that feel personal and close. However, this same emotional component can easily become manipulative when brands exploit trust, manufacture narratives, or push low-value products under the guise of genuine connection.

The main takeaways are that authenticity matters and parasocial bonds can’t beat a mediocre offering. Brands that prioritize meaningful engagement over aggressive monetization can create long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with their audiences. Those who abuse the parasocial bond risk backlash, lost credibility, and long-term damage to their reputation. As with any powerful marketing tool, success lies in balance—leveraging emotional connection while delivering quality.